An American in Paris Scribe Craig Lucas on Chatty Neighbors, Intimidating Gershwins and What Makes Him Cranky

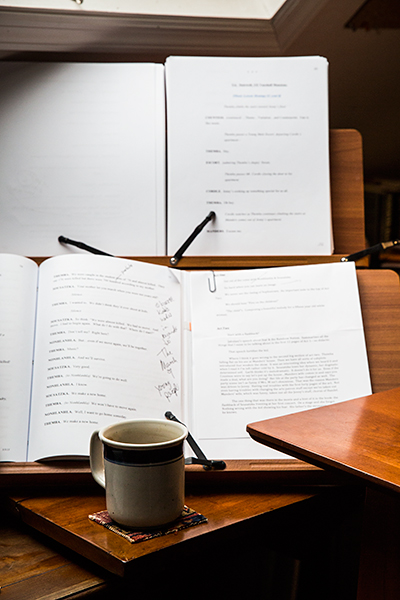

Craig Lucas’ home in upstate New York is filled with sunlight, art, books, dogs and lots of laughter. He is warm, open and unceasingly generous to guests. (Which of the no fewer than four different types of milk would you like in your coffee?) The boxes under his desk (an organizing trick learned from Sondheim, natch) offer a glimpse at his immense and diverse body of work, which includes plays (Reckless, Blue Window, Small Tragedy, The Singing Forest, The Dying Gaul, Pulitzer finalist Prelude to a Kiss and more) as well as screenplays (Longtime Companion, The Secret Lives of Dentists) musicals (the book for The Light in the Piazza), and we haven’t yet mentioned his opera librettos, directing resume or that he started out as a Broadway chorus boy. Here, Lucas talks about his writing process, particularly for his Tony-nominated book for the new musical An American in Paris.

What time of day do you get your best work done?

The morning. Because of deadlines and the way that people tend to call after a certain hour, I get up really early. Mornings are good for me, but if I have to write at night, I will. With musicals, you’re out of town and they want the changes in the morning, so often I go back to the hotel and write late into the night.

Do you write every day?

No, but I feel better when I write. The hardest thing is doing a first draft. I have found that the less I say to other people about what I’m doing, the more the need to write comes out.

Do you have a writing ritual?

I feed the dogs and take them out. I drink my coffee. If I’m really up against a deadline, I will not even check my email. I generally do look at the email, though—it’s nice to get the fingers to start to work. [Fake typing.] “Thanks for thinking of me.” Or, “Oh, I’m sorry a tree fell on your house. God’s a sadist.” And then you're already typing, so all you have to do is trick yourself into starting. That’s the only hard part.

What playwright inspires you?

What essential items do you like to have on hand when you write?

I just need a computer. Not much else. I have to have a certain sense of play and of being troubled by a situation or a question. I can’t write into something I’m absolutely clear about. I think what you need is both passion and a little bit of disinterestedness. A little oh-f*ck-‘em-if-they-can’t-take-a-joke attitude. I think it helps to have a bit of contempt for conventional thinking. I’m so grateful to audiences, and I write to reach them, but there’s also a part of me that’s just mad at them. I go to the theater sometimes, and I think, “Oh, people!”

What advice do you wish your younger self had followed or been given?

I was not prepared for how much work you have to do all the time on everything. I don’t think I would have taken advice as a young man because I was so unformed and had so many things I had to get over. I was raised to believe that I was special and I didn’t have to work hard, and that’s just not true. But everything happens the way it does. Sometimes things that seemed terrible turn out to be the best things that ever happened.

What was the biggest challenge in adapting such a well-loved movie?

There’s no competing with the movie. I was fortunate that the producers really wanted to investigate what the movie didn’t unpack. It's filled with clues: Why does Jerry stay in Europe? Why does Adam stay? Why is Lise not in love with Henri? Why was she hiding? What do the French make of these people who are embracing their city at such a difficult time?”

What’s the reality of the typical writer’s Paris fantasy?

For me the writer’s fantasy about Paris is true. Did you know there are more English bookstores in Paris than in Manhattan? One of the things that I loved about New York when I first moved here was all of the bookstores. They’re gone. So I’m cranky now. Paris is absolute heaven.

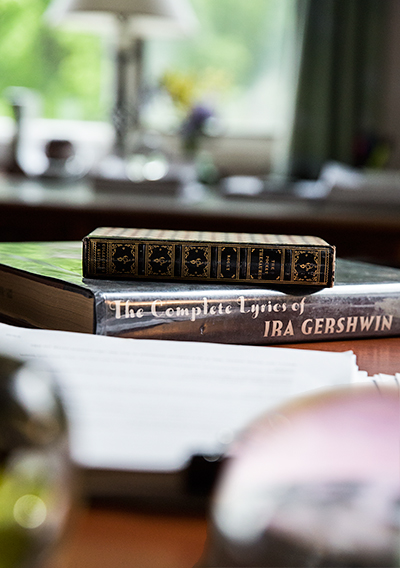

How did you feel having the Gershwins as your collaborators?

Mike Strunsky [Ira Gershwin’s nephew and trustee] is fantastic. He loves these songs. He was such a champion of what we were doing. The other [Gershwins] were enthusiastic, but they’re very intimidating. They come in a big group and there are lawyers. I kept making jokes as is my wont. [Director] Chris Wheeldon finally slipped me this little note that said, "They don’t get your jokes."

What’s the secret to being so prolific?

I’m really happy with the things I get to work on. Some weird thing happened: Everybody woke up on the same morning and said, “Get Lucas!” It started around 2011 and 2012. I was six years sober. I think my reputation for being a giant pain in the ass was starting to lift.

How has your life as a writer changed since you got sober?

I’m clear-headed. I’m not muddling through. I’m much better at listening to people’s suggestions. The producers on An American in Paris are smart and their notes are smart; you’d be stupid not to listen. I think as a young writer, I was like, “This is MINE! This is the way I wrote it!” Well, who cares? Steal a line from the usher!

What play changed your life?

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received about writing?

It was from my teacher Anne Sexton. She gave me a recommendation to go to graduate school at Yale and I got in. Then she called me and said, “Don’t go! You are stubborn and you see things your own way.” That was really good advice. I wasn’t ready for graduate school. If I had been in that class with Chris Durang and Wendy [Wasserstein] and those people, I probably would have withered up and died of intimidation. I went off by myself and hung out in a dark corner for a while until I had a self.

What’s the nitty, gritty hard work of being a playwright that no one ever told you?

It’s very hard for people to understand that when you’re home, you’re working. My neighbors come to the door all the time just to chat. I’m like, “I’m working.” And they’re like, “OK. Can I come in?”

What’s something aspiring playwrights should do, see or know?

They should know that when I finished my play Reckless, I sent it to a very famous Tony-winning director, who wrote me back and said, “This play makes no sense at all.” I have saved this note. I didn’t give up, but I did get an ally. I met a young director who was my age and liked my work, so I had another person to keep me from jumping off of a building. Find people who are at your stage of development instead of trying to get your play to Joe Mantello or some other high-powered director. Develop an aesthetic with your friends. That worked for me.

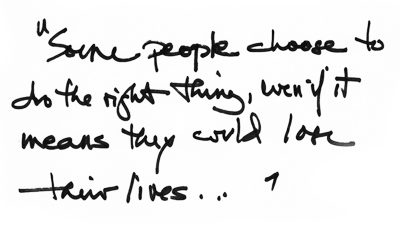

What's your favorite line in An American in Paris?